The sun has always been our nearest “final frontier.” While humans have been able to collect samples from the moon—and even walk around on it—the sun's incredible heat has made this impossible. At least, until now. For the first time in mankind's history, scientists have been able to gather samples from the sun's corona.

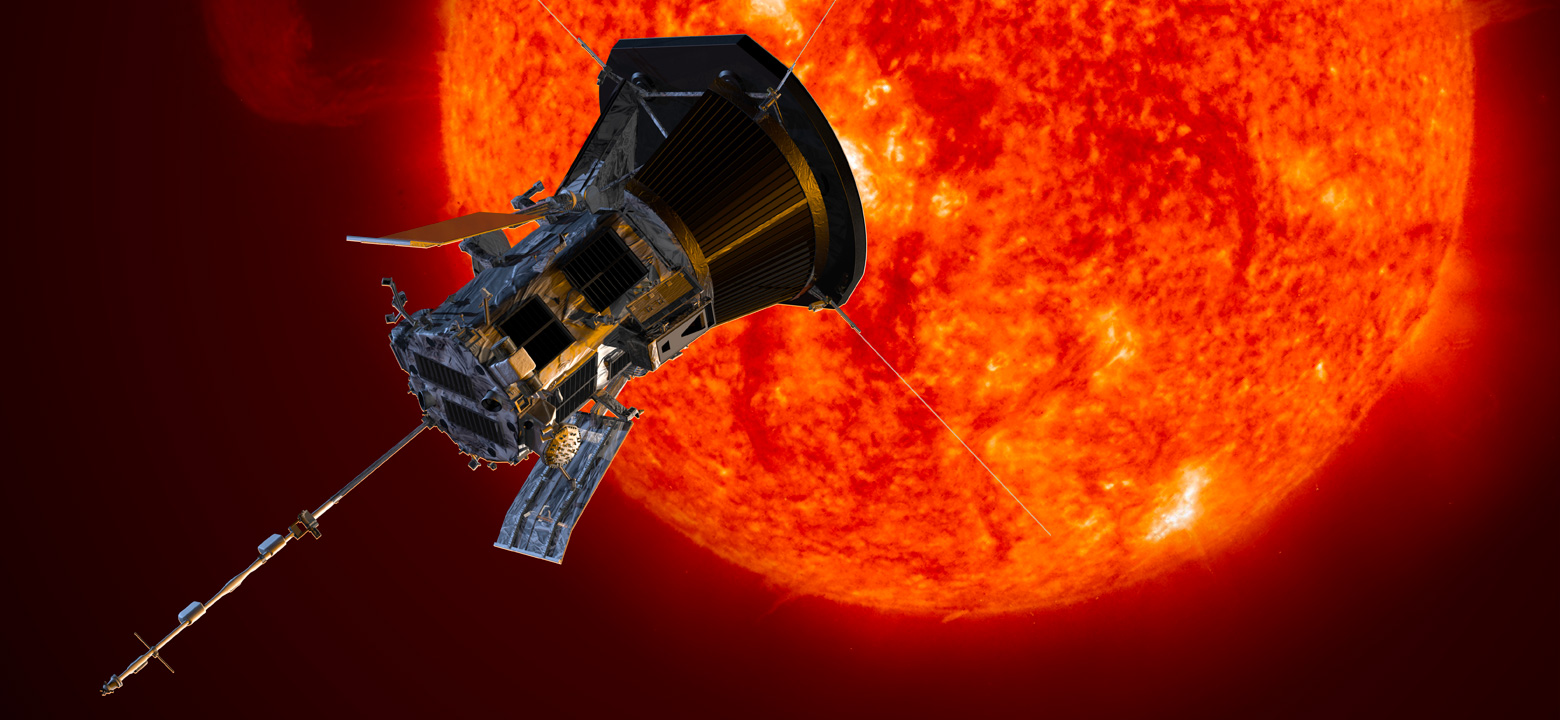

The Parker Solar Probe launched three years ago with the goal of getting closer to the sun than ever before. Of course, “close” is very relative here—at the closest point of approach, the Parker Solar Probe will come within roughly 3.8 million miles of the solar surface. While this sounds far, the immense size of the sun (about 864,000 miles in diameter) means that it's really very close. The only other craft to get anywhere near that close was the Helios 2, which managed to come within 27 million miles of the sun's surface.

The Parker Solar Probe is a craft roughly the size of a small car—only about 1,400 pounds in weight. Nonetheless, this small, lightweight craft launched using one of the world's most powerful rockets, and for good reason. It takes a lot of energy to reach the sun.

Along the way, the craft passed near Venus to perform a “gravity assist.” This is a flyby technique where a craft uses another body's orbit in order to affect its flight. Imagine a volleyball game. The ball is a spacecraft, the players are planets, and the players' hands are their gravitational fields. The ball moves toward one of the players with its own momentum until it's struck by a player's hands. This makes the ball change direction and move away from the player with more or less momentum. This is what the Parker Solar Probe did with Venus. The Probe didn't actually strike the planet, but the idea is the same—using Venus' gravity field to help it get to where it needed to go. This will occur multiple times during the mission as the Parker Solar Probe makes a spiraling approach to the sun.

Though the sun's corona reaches millions of degrees (interestingly, it's even hotter than the sun itself), the Probe didn't melt. This is because, despite the fact that the corona's particles are fast-moving, there's a lot of space between them. That means that they didn't have enough contact with the Probe to transfer enough heat to damage its carbon-composite heat shield.

When the Probe comes closest to the sun, it enters its Science Phase. At this point, its resources are dedicated to making observations. The remainder of the craft's orbit is dedicated to relaying those observations to scientists in preparation for its next Science Phase.

The sun has largely been a mystery for a long time, and the Parker Solar Probe is helping to reveal some of its secrets and expose entirely new ones. As mentioned above, the corona is much hotter than the sun itself, and scientists hope the Probe can provide some insight as to why that's the case.

In 2019, the Probe uncovered “switchbacks,” which are magnetic zigzags within the solar wind. They cause very sudden, 180-degree flips in the magnetic field before switching back as little as seconds later. Initially, nobody knew where they originated. Now, the Parker Solar Probe has provided a likely culprit: the sun's surface.

Its recent approach to the solar corona has resulted in another interesting discovery. The sun doesn't have a solid surface, but it does have gravitational and magnetic forces that allow it to hold its shape. At a certain point, these forces become too weak to continue to do so. This is named the Alfvén critical surface. It marks the border between the solar atmosphere and solar wind. Until recently, nobody was really certain where this boundary was, though estimates pegged it at roughly 4.3-8.6 million miles from the sun's surface. During its spiraling approach, the Parker Solar Probe managed to pass within the corona several times. This indicates that it isn't a smooth sphere—it has ripples, peaks, and valleys of its own. By correlating these shapes with solar activity, scientists may be able to figure out how events on the surface impact the solar wind.

The Probe is expected to fly through the corona again during its next flyby, in January.

While these discoveries are amazing, the Parker Solar Probe's mission is far from over. It still has several passes to make, and a lot more information to gather. Its mission is anticipated to run until 2025, with a total of seven gravity assists from Venus.